Preston Sturges's "Sullivan's Travels"

There's a lot to be said for making people laugh," says the famous movie director, whose specialty has been such deep intellectual fare as Hey Hey in the Hayloft and Ants in Your Plants of 1939. He's going to be married soon, and we might say that he has been blessed as the Ancient Mariner never was. A happier and a wiser man he rose the morrow morn, and after a stay as a member in a chain gang in the swamps of the deep South, to boot. "Did you know that that's all some people have?" he says. "It isn't much, but it's better than nothing in this cockeyed caravan. Boy!"

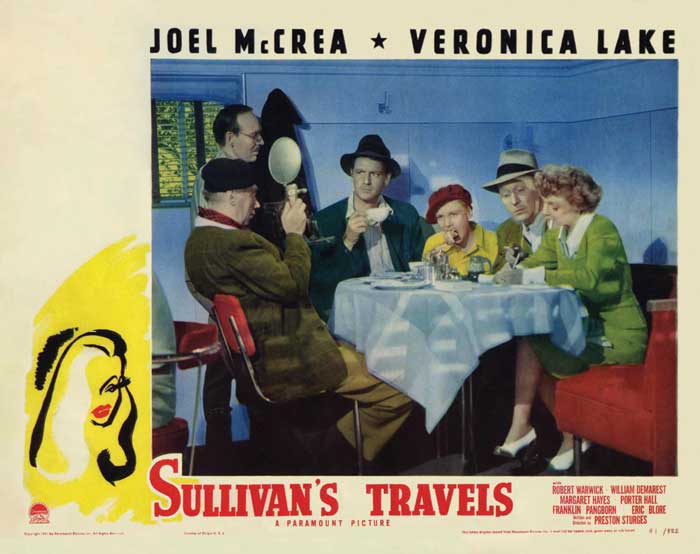

Those are the last words in Sullivan's Travels (1941), what I think is the best screwball comedy from the greatest master of the kind, Preston Sturges. It is a delightful tale, all the more comic for treading near the edge of tragedy, as it shows us, especially in one long sequence without a spoken word, that many an American still was homeless and penniless in the wake of the Great Depression.

John L. Sullivan, played by the clean-cut, tall, and boyishly all-American Joel McCrea, is a director with a nagging conscience. His ambition is to make a movie that speaks to the real suffering of the poor, a documentary, something serious, something relevant to the times, showing labor and capital at each other's throats so that both die at once. It is to be called O Brother, Where Art Thou?—and yes, the Coen brothers were thinking of this film when they made their own Odyssey-romp by that name (2000).

Not an Interesting Subject

Sully's friends and his boss at the studio don't want him to do it. Why give up such success? And what does he know about suffering, after all? He's a boarding-school and college boy; let him stay with what he knows. But that very demand prompts him to try to learn about what he has never experienced. He decides to dress as a tramp and ride the rails, wandering about the country, seeking out the poor. Sturges here treads carefully and deftly between sympathy for what Sullivan feels and a gentle but persistent criticism. For Sullivan may be playing the fool, sentimentalizing the poor and setting himself up to get perhaps more poverty than he bargained for.

His own valet (played with a fine British deadpan by Robert Greig, a Jeeves to Sully's Bertie Wooster) is appalled to find him in tattered clothes. "Fancy dress, I take it?" says the valet, shaking his head. "I have never been sympathetic to the caricaturing of the poor and needy, sir."

Sullivan stands his ground, saying that he is serious, and that he wants to make a picture about them. But the valet demurs. "The subject is not an interesting one," says he, but not because he has made no study of it himself. On the contrary.

"You see, sir, rich people and theorists, who are usually rich people," says the valet—and here we may glance at the comfortable members of Fabian Societies and pot-bellied professors seasoning their filet mignon with a dash of Marx—"think of poverty in the negative, as the lack of riches; as disease might be called the lack of health. But it isn't, sir. Poverty is not the lack of anything, but a positive plague, virulent in itself, contagious as cholera, with filth, criminality, vice, and despair as only a few of its symptoms. It is to be stayed away from, even for purposes of study. It is to be shunned."

That is not Sturges's last word on poverty, far from it, nor may a good Christian rest easy here. But there is no sentimentality, and no convenient reduction of poverty to a mere economic condition, easily corrected. Poverty reaches into the dark and dreadful corners of the soul. The poor are sinners, too.

The Girl

Well, Sullivan persists, the essential ingenu, and a series of unlikely likelihoods follows in his steps, many of them of a rollicking, belly-laugh hilarity. A ride through the bumpy fields at more than a hundred miles an hour, for example, in a whippet-tank driven by a thirteen-year-old and suitably helmeted farm boy on his way to school—Sullivan is trying to get free of the studio people who have been following him in a "land yacht," looking out for his safety.

But the crucial early turn in the film comes when a coincidence or two lands Sullivan, still dressed as a tramp, back in Hollywood, and in a greasy little diner he meets a girl (the sultry Veronica Lake) who is on her way back home to the Midwest. She doesn't know that he is a rich and famous director, so she buys him a simple breakfast of ham and eggs and coffee.

Sturges does not let us look at her as a sweet girl with a heart of gold who has ended up in the wrong place. The Girl—we never learn her name—had gone out west to realize her dream to act in the movies, but now she speaks as someone disillusioned by the seamy and selfish underside of the industry. To make your way, you have to cozy up to the men in power. "Just think," she says, "if you were some bigshot like a casting director or something, I'd be staring into your bridgework saying, 'Yes, Mr. Smearcase. No, Mr. Smearcase. Not really, Mr. Smearcase! Oh, Mr. Smearcase, that's my knee!'" And she takes a puff of her cigarette as her voice drops.

Of course he takes an interest in her, and after a short stop back at his posh manor, where she pushes him into the swimming pool for being a "big dope," he and she take to the rails together, she dressed as a boy in oversized clothes. She has to go, she says, because somebody has to take care of him. In fact, they take care of each other, so that the usual screwball comedy mode—big, foolish, intelligent man against wily and beautiful woman—is tempered by a real and surprising warmth, and an unstated appreciation of the sexes in their strength; the visual contrast between McCrea (6' 3") and Lake (4' 11") is itself comical and charming.

A Seeming Success

Sturges, who also wrote the screenplay, tells the story of their adventures with a touch that ranges from the lighthearted to the deeply poignant and sorrowful. We have scenes of quick and snappy dialogue, and words that say more than their speakers intend—"Amateurs," grunts one tramp to another in a train-car as Sullivan and the Girl barely manage to run and climb into it as the train pulls away. "What do you think of the labor situation?" Sullivan asks him. The tramp's reply is to spit out the straw between his lips, and walk away.

We also have the best of what the old silent films had to offer, without words or captions, since none are needed: Sullivan and the Girl getting surprised by bedbugs or lice in the hay of the train-car; the sad and careworn faces of men and women, old and young, and children too, as they are all packed together by the hundreds on the floor of a charity house; the stew they gobble down next to an old toothless man whose gums work like a great mill; the urgent and ineffectual noise, told by music alone, of the preacher who urges the masses to leave their wicked ways; and one moment when Sullivan and the Girl, alone, their backs to us, look to westward in the evening sun, and he places his arm around her waist.

The enterprise seems to have been a success, as Sullivan and the Girl return to Hollywood, where his studio boss has made lemons into lemonade, using it all for publicity for that great human film to be made, O Brother, Where Art Thou? Sullivan, remembering the people who did him a good turn when he was a tramp, says he will commemorate the event by going out one last time, at night, with new shoes on his feet and a load of five dollar bills in his pocket, to hand them out one by one to the poor people he comes across. His charitable walk takes him along the train tracks, where a tramp has followed him, noting the money—and the shoes.

What happens then, I do not wish to give away, but I will say that not one viewer in a thousand will guess it. Let it suffice to say that Sullivan ends up among people with less to their names than any he had met before, by way of property or respect from their countrymen.

Loads Lightened with Laughter

In one scene, for my money the most powerful church moment in Hollywood history, a kindly black preacher, a basso profondo, prepares his congregation for a special movie entertainment that night, as a big white sheet is undraped in front for a screen, and the projector is ready, along with a smiling lady at the pump organ for the music.

They are going to have guests, too. The preacher begs his all-Negro congregation not to put on airs, and neither by word nor look to make these guests feel unwelcome, or to act "high-toned" before their visitors tonight, because "we is all equal in the sight of God," and Jesus said, "Let him who is without sin cast the first stone," and "The blind shall see, and the lame shall leap, and glory in the coming of the Lord!" And then, with the organ playing, he leads them in singing "Go Down, Moses" as, led by a warden with a rifle, the men of a chain gang enter the church, shuffling and clanking, gaunt, slow, dispirited, but doffing their hats (if they have them) as they enter.

Sullivan is among them, and not by design.

What great cinematic work they watch, I will not say. But the preacher, his people, and the prisoners burst out into peals of raucous laughter, while Sullivan looks about him nonplussed, and then he, too—the moment is magical—in all his misfortunes, laughs again, laughs loud and long.

What Sturges has done, while satirizing "relevant" movies with a social message, is to produce the best of them all. People need to laugh, says Sullivan in the last words of the movie, because that's all that a lot of us have. "To the memory of those who made us laugh," reads the opening shot, "the motley mountebanks, the clowns, the buffoons, in all times and in all nations, whose efforts have lightened our burden a little, this picture is affectionately dedicated."

And we Christians may go farther, to sing with the kindly black people in the church at night, and to be fools for Christ, let the world think what it will.

Anthony EsolenPhD, is a Distinguished Professor at Thales College and the author of over thirty books and many articles in both scholarly and general interest journals. A senior editor of Touchstone: A Journal of Mere Christianity, Dr. Esolen is known for his elegant essays on the faith and for his clear social commentaries. In addition to Salvo, his articles appear regularly in Touchstone, Crisis, First Things, Inside the Vatican, Public Discourse, Magnificat, Chronicles and in his own online literary magazine, Word & Song.

Get Salvo in your inbox! This article originally appeared in Salvo, Issue #57, Summer 2021 Copyright © 2026 Salvo | www.salvomag.com https://salvomag.com/article/salvo57/fools-indeed