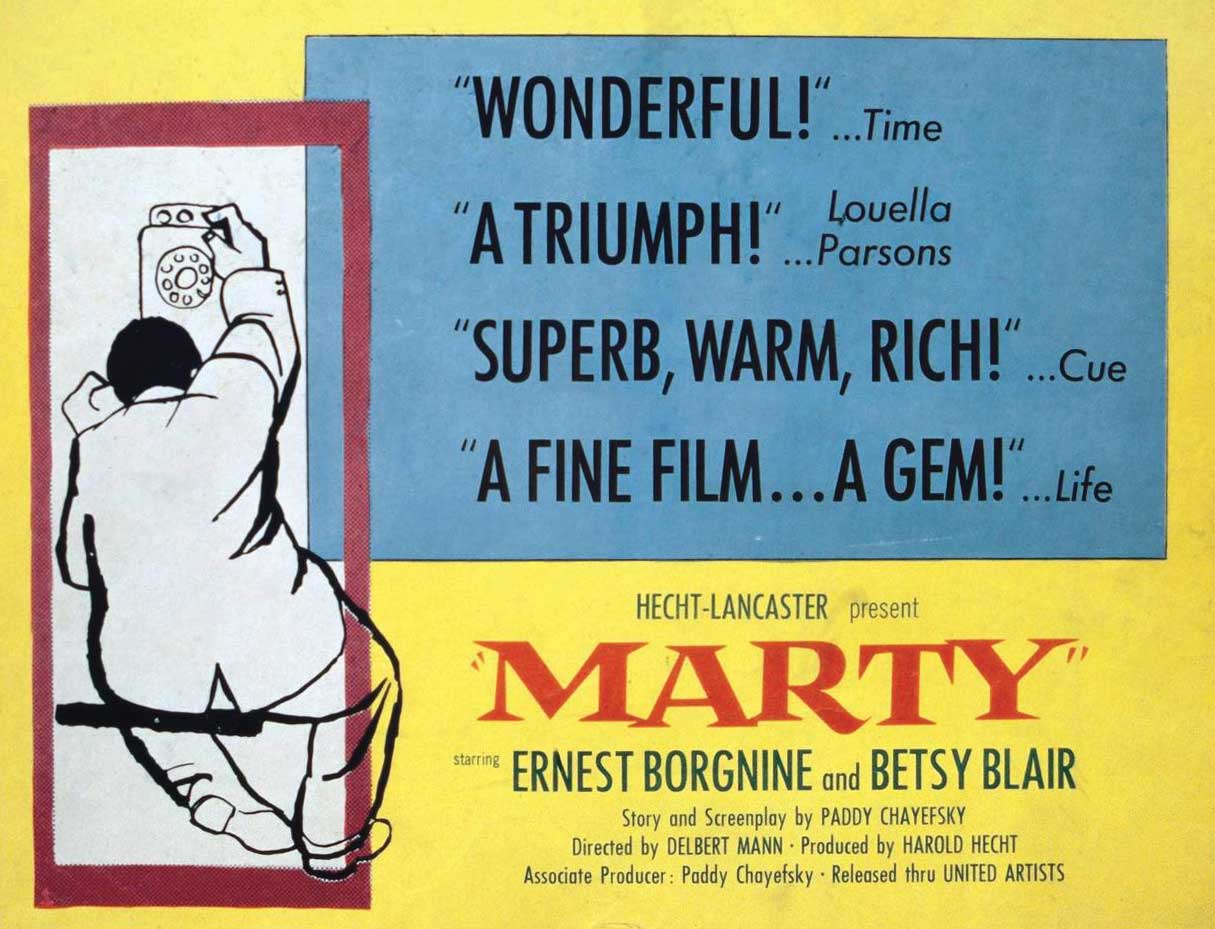

Marty

Many are the reasons why Marty, winner of the Best Picture Oscar for 1955, would not be made now. It's in black and white, that medium that throws a special emphasis upon the human face and hands; in this case, the kindly, lonely, too-often-hurt face of a fat, hard-favored butcher named Marty (Ernest Borgnine). It asks us to care for the lives of two very ordinary people, Marty and Clara, whom he meets by accident at a dance hall. Marty overhears her blind date trying to pay a stranger five bucks to take her home—the date has run into a hot number he knows from before, and doesn't want to be leashed to "a dog," especially since he's a busy young doctor and hasn't had a free weekend in two months.

What happens in the movie could never be captured in a video game, since its field is the human soul; the two lonely people begin to fall in love with one another, behind their shyness, their sadness, and even Marty's awkward attempts to comfort. "You ain't such a dog as you think you are," he says, and then, realizing his misstep, adds, "and maybe I ain't such a dog, either, as I think I am."

There's not one false step in the whole film, not one word out of place, not one shot taken for a cheap effect, not one overdone measure of music. As I said, Marty would not now be made. It belongs to an era which was not innocent, but which possessed a nostalgia for innocence. Viewing it now, though, I see that Paddy Chayefsky's screenplay wasn't just heartwarming. It presented a critique, subtle and deeply perceptive, of what we now call the Sexual Revolution.

That revolution was in the making then, just as the supermarkets were coming—a somber threat on the horizon that Marty, who wants to buy the butcher's shop where he has been working, must acknowledge and make allowances for. Chayefsky shows us that revolution from its direct effects on Marty's friends, all of them losers who fancy themselves ladies' men, guys who would never dream of looking twice at Clara, and from the collateral damage it has done to the hero and the heroine.

Two Sides of the Street

The whole movie takes place within a twenty-four-hour period. It's late on Saturday night, and Marty and Clara have left the glitzy Stardust Ballroom. They've done nothing but talk for hours, snacking at a little railroad-car diner, and walking the streets of Brooklyn. Marty's friend Ralph pulls up in a car and yells for him, "Hey, Marty!" Marty crosses the street to find out what he wants. The staging is perfect: on one side of the busy road, Clara, a chemistry teacher, standing alone and waiting; on the other, a rakish Ralph (Frank Sutton, Sergeant Carter in Gomer Pyle) trying to persuade Marty to come along for the ride, because he's got a girl extra in the car. "Come on, Marty!" he says. "These are hot numbers—they're nurses, boy, nurses, and they know all the moves. Come on, help a fellow out!"

Note that the sexual is suggested, and utterly undermined, by the clinical. They're nurses, so they are used to seeing naked bodies. They know their anatomy. They can look at things with a cool detachment. Ralph himself has no real concern here for either Marty or the women, but only for the things they will presumably be doing soon.

"I can't, Ralph," says Marty. "I have a girl over there."

"So what?" says Ralph. "Give her the brush-off!"

Just like that. Lust is hard of heart indeed.

"I can't do that to her," says Marty. "Some guy already gave her the brush-off tonight. I'm sorry, Ralph." Ralph isn't given time to think about it. A faceless woman from the back of the car shouts, "Are we going or not? I don't want to wait around here all night!"

Ralph drives off. Marty will see him the next day. "How was your night, Ralph?" he asks. Ralph is sitting, hunched over a table at the diner. He looks as if someone has slipped him a downer. "Oh, it was great, Marty," he drones, in utter lassitude, bearing out the wisdom of the old medieval commonplace, omne animal post coitum triste est: every living creature after copulation is morose.

Mass & Afterwards

Before Marty leaves Clara at her house, he asks if he can see her tomorrow—Sunday. "I'll be getting out of Mass around eleven," he says. "Did I mention I was Catholic?" Yes, he mentioned it already. "I'm not free till around two," she says, "because I go to Mass at noon." Going to Mass is one of the crucial motifs of the film, though what it means to the other characters isn't clear. Marty's cousin Thomas and his harridan of a young wife go to Mass. Marty's friends all go to Mass.

But soon after, we find them in Marty's apartment, lounging about. One of them has a magazine and is crowing about the pictures in it. "These are real actresses, you know!" he says. Marty is embarrassed and irritated. "What are you doing with that here? My mother could be walking into the room any minute!"

Marty's best friend, Angie, saw him with Clara the night before, and when Marty tried to introduce him, he hardly glanced at the girl. "You were very rude to her last night, Angie," says Marty, but Angie doesn't care. What does Marty see in her, anyway? She was a dog. Marty's mother, who met her briefly, says she doesn't like her either—she's been gotten to by her sister, Thomas's difficult mother, who is being thrown out of the house to live with her and Marty. So she views Clara as an interloper. "I don't like her, Marty," she says. Why not? "I don't know, I just-a don't like her."

So Marty's brief hours of happiness and hope have been rained on. He's supposed to call Clara that afternoon. He doesn't call. We see Clara with her mother and father, in their living room. They're watching Ed Sullivan. Clara stares into space, crestfallen.

Flesh & Blood

Meanwhile, Marty is with the boys. One of them, in a comically gravelly and over-masculine voice, drones on and on about pulp novelist Mickey Spillane. "That Mickey Spillane," he says, "sure knows how to handle dames." Dames, broads, tomatoes. The boys are none of them particularly good looking. Angie is a skinny little fellow with the eyes of a ferret.

"What do you want to do tonight, Angie?" asks one.

"I don't know. What do you want to do?"

We hear these as voices, while the camera focuses on Marty's weary countenance. On and on they go, these pathetic and lonely people, who think they know all about sex, but don't know the first thing about love, much less about a flesh and blood woman like Clara—flesh and blood, not the wraiths of a diseased imagination.

Finally Marty bursts out in anger. "What do you wanna do, what do you wanna do—I should have my head examined! Here I am hanging out with you guys and I could be with a nice girl I really like!" He rushes into the diner. Angie follows him to pull him back.

"I don't care what you think of her, Angie; I don't care what Mama thinks, or Thomas. I like her, and I'm going to ask her to go out with me tonight, and if we go out enough and she still likes me, I'm going to get down on my knees and beg that girl to marry me!" And he goes into the phone booth. "Hello, Clara? It's me, Marty." And the movie ends.

Drawn Near

But at one moment in the movie it seems as if the acid might just get to Marty himself. He has taken Clara back to his apartment. Mama is out. He tries to kiss her—and she pulls away, frightened. The poor simple butcher bursts out in anger and disappointment, "One lousy kiss, that's all I wanted, just one kiss, was that so much to ask?" He sits down, head in his hands. Clara approaches from behind and tries to explain. She didn't know how to handle the situation, she says. Marty is comforted. "I think," says Clara, "I think you are the kindest man I've ever met."

A little while later, Marty and Clara are in front of her house. Now it's very late indeed. It's the moment for saying goodbye. They look at one another, awkwardly. And Marty and Clara draw near, and he kisses her—the lightest touch of the lips. Even that is too much for their hearts to bear; and Marty, the muscular, balding, homely butcher, clutches Clara to his breast, as you would clutch a beloved child to save her from danger. It is one of the most poignant, and most genuinely sexual, moments I have ever seen in the movies.

That, dear reader, is what the sexual revolution, that reversion to rutting and ennui, would make impossible and incomprehensible.

Anthony EsolenPhD, is a Distinguished Professor at Thales College and the author of over thirty books and many articles in both scholarly and general interest journals. A senior editor of Touchstone: A Journal of Mere Christianity, Dr. Esolen is known for his elegant essays on the faith and for his clear social commentaries. In addition to Salvo, his articles appear regularly in Touchstone, Crisis, First Things, Inside the Vatican, Public Discourse, Magnificat, Chronicles and in his own online literary magazine, Word & Song.

Get Salvo in your inbox! This article originally appeared in Salvo, Issue #60, Spring 2022 Copyright © 2026 Salvo | www.salvomag.com https://salvomag.com/article/salvo60/marriage-story