The Archaeology of Daniel & Babylon

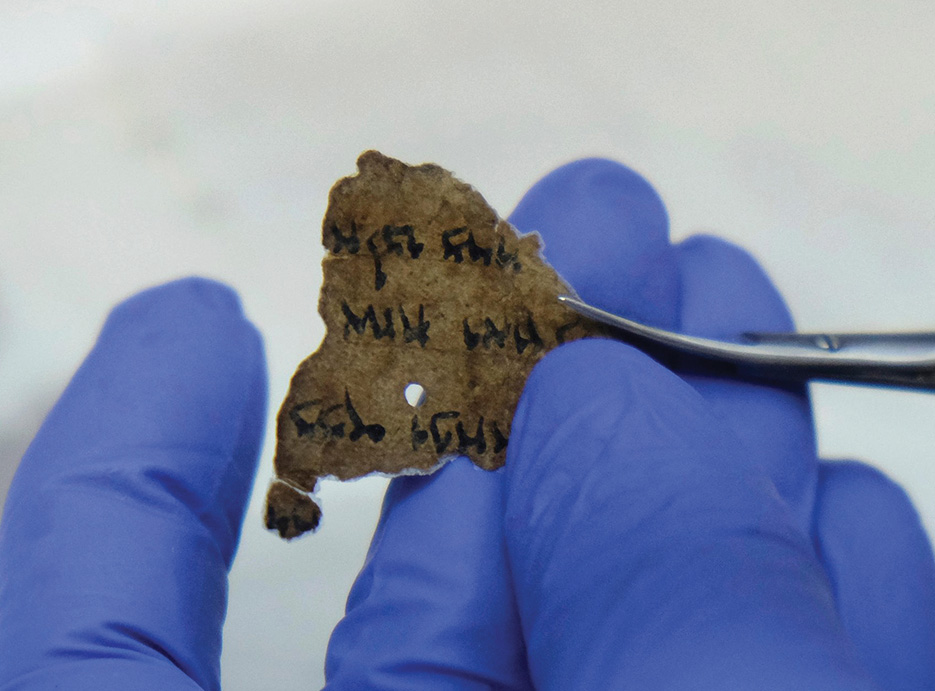

The events recorded in the Old Testament book of Daniel take place during the Neo-Babylonian empire, primarily in the city of Babylon, in approximately 605–536 BC. The earliest manuscript representing the book, 4QDanc from the Dead Sea Scrolls, dates to ca. 125 BC.1 Due to the later date of the manuscripts and the content of the book, many scholars in modern times have argued that Daniel was written in the second century BC by pseudonymous authors in Judea.2 Starting from this idea of a text composed more than four centuries after the stated setting by a person or persons who lived in a country far removed from Babylon, many scholars have claimed that the text of Daniel contains numerous historical errors or inventions. However, a survey of archaeological discoveries related to the book reveals that the narrative contains remarkably accurate descriptions of people, places, customs, and events in sixth-century BC Babylon.

Babylon & King Nebuchadnezzar

The story begins with the Babylonians’ capture of Daniel and others in the third year of King Jehoiakim of Judah, ca. 605 BC.3 Although no direct archaeological evidence of Jehoiakim has been found, a Hebrew seal belonging to his grandson, which translates to “belonging to Pedaiah, son of the king,” has been discovered, and an official in his administration named Gemariah, son of Shaphan, is attested by a Hebrew bulla (a type of seal).4 During the reign of Nebuchadnezzar,5 Babylon was probably the largest city in the world, encompassing nearly 900 hectares across both sides of the Euphrates River, with a population of approximately 200,000. The site was rediscovered in 1616, and archaeological projects began in 1811, eventually uncovering much of the ancient city as well as over 5,000 tablets.

Excavations have demonstrated that Babylon in this period was surrounded by both an inner and outer city wall, as well as a moat which encircled the city. On the north side was the most famous gate in the city, the Ishtar Gate. It stood at least 12 meters tall and was decorated with a lengthy honorific inscription in which Nebuchadnezzar repeatedly praises himself and his exceptional accomplishments, calling himself “the pious prince appointed by the will of Marduk, the highest priestly prince, beloved of Nabu, of prudent deliberation, who has learnt to embrace wisdom…the untiring Governor…the wise, the humble, the caretaker.”

Daniel references construction carried out by Nebuchadnezzar and notes his exceptional pride.6 From archaeological excavations and Babylonian texts, such as inscribed bricks and cuneiform cylinders of Nebuchadnezzar, it is known that he restored multiple temples, finished the Etemenanki ziggurat, rebuilt the Ishtar Gate and the Processional Way, remodeled the Southern Palace, and built the new Northern Palace.

Yet notably absent from Daniel is any reference to the iconic “Hanging Gardens of Babylon.” Although classified as one of the ancient Wonders of the World and located in Babylon according to later sources such as Diodorus Siculus of the first century BC and Josephus of the first century AD (sourcing Berossus), earlier historians such as Herodotus and Xenophon make no mention of these gardens. No mention has been found in the records of Nebuchadnezzar, nor has any archaeological evidence been discovered. Many scholars now consider the legend of these gardens to have originated in texts and artwork describing waterworks and gardens in Nineveh.7 The lack of any mention of royal gardens in Daniel is significant in that it suggests the author was familiar with the real Babylon of the sixth century BC, rather than relying on incorrect information that surfaced around the third century BC and was then repeated in late antiquity.

The Exiles

The presence of exiles from Judah living in Babylon and the surrounding region is also known from archaeological discoveries. One of the most important artifacts related to the Babylonian exile is a tablet of the Babylonian Chronicle, sometimes referred to as the Jerusalem Chronicle. A section of it addresses year seven of Nebuchadnezzar II, stating that he took the king of Judah (Jehoiachin) captive to Babylon and then installed a new king of his choosing (Zedekiah) to rule over the conquered kingdom.8 The Babylonian Ration List tablets discovered at Babylon mention that this king Yaukin (Jehoiachin) of Judah and his sons received rations from the royal house during their captivity, while also referring to other unnamed Judean officials. All these details are consistent with Daniel and other biblical texts.

Information from the book of Kings, taken together with the ration tablets of Jehoiachin and the Prayer of Amel-Marduk tablet, indicate that Jehoiachin was released from prison and given a daily allowance by the new king of Babylon, Amel-Marduk. A son of Nebuchadnezzar, Amel-Marduk had been jailed by his father. While in prison, he wrote a prayer which has been preserved on a cuneiform tablet. After Nebuchadnezzar died and Amel-Marduk was released and crowned king, he freed Jehoiachin, although Jehoiachin remained confined to Babylon. At the end of a short reign of fewer than two years, Amel-Marduk was murdered by his brother-in-law Neriglissar, whom Jeremiah the prophet mentions as a leading officer of the king.9

Judean exiles outside of the royal family are also attested through the Al-Yahudu tablets, which date as early as ca. 572 BC. These cuneiform tablets describe a community of exiles from Judah living in a rural village near Borsippa, southwest of Babylon. The tablets are written in Akkadian with some Aramaic notation, indicating that the exiles had adopted or made use of the local language.10 These tablets, which focus on economic and legal issues, such as agriculture, commerce, property leases and sales, loans, military service, taxes, and slavery, also reflect adoption of Babylonian laws and customs. Although many of the names are clearly Hebrew, no mention of Israelite religious practices has been found in these texts, indicating that syncretism was part of adaptation to life in Babylon for many of the people.

The Fiery Furnace

Daniel also describes strange and brutal laws, such as death by burning in a furnace for anyone who would not bow down and worship the golden image Nebuchadnezzar had built.11 This custom of execution by burning for religious blasphemy is not only attested in ancient Mesopotamian texts from centuries before the time of Daniel to at least 300 years after, but a sixth-century BC letter from the Sippar temple library in the Babylon region during the reign of Nebuchadnezzar describes this exact practice.12 The place of burning was an oven or kiln, and the word used in the letter is the equivalent of the Aramaic word Daniel uses for the fiery furnace. This letter states that those who commit blasphemy against the gods must be thrown into the kiln to be destroyed by intense flames. This was apparently a lime kiln which had an opening at the top in which to place materials for melting, and it appears to be the method used to punish Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego.

Belshazzar

Following the death of Nebuchadnezzar, Daniel lived through a tumultuous time in the empire, during which four different rulers ascended to kingship over a period of six years. Eventually, Nabonidus was placed on the throne. According to Daniel, during the time of Nabonidus, a king named Belshazzar curiously offered Daniel the third-highest position in the kingdom, rather than the second, as a reward for reading the terrifying “handwriting on the wall.” This section of Daniel and its account of the otherwise unknown king named Belshazzar was harshly criticized by scholars as unhistorical fiction prior to archaeological discoveries that confirmed the existence of a Babylonian king named Belshazzar.13

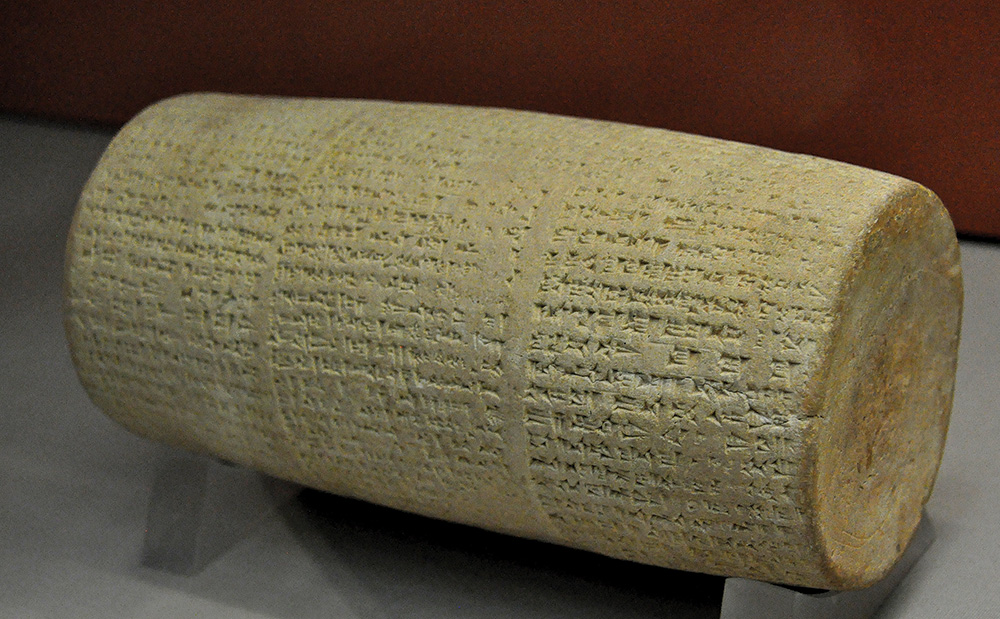

Eventually, a cuneiform cylinder was found at the Temple of Shamash in Sippar with an inscription about Nabonidus of Babylon which named his firstborn son as Belshazzar.14 Another important cuneiform text, written after Cyrus gained control of Babylon, explains how the firstborn son of Nabonidus was entrusted with the kingship in his father’s absence.15 Other Babylonian documents also make it clear that Nabonidus was away from Babylon in 539 BC when the city fell. Further, the fifth-century BC historian Xenophon records that the son of a Babylonian king, who was also called a king, was ruling in Babylon when the Persians conquered the city.16 Together, these ancient sources show that Belshazzar had been installed as king of Babylon while his father was away and that he was ruling Babylon when the alliance of the Persians and Medes captured the city. So Nabonidus was still alive and was thus first in the kingdom, with Belshazzar second. This explains why Daniel was offered the third-highest position as a reward.

The Fall of Babylon

One of the most important events in ancient history, this capture of Babylon by the alliance of Medes and Persians is also briefly described in Daniel.17 Daniel notes that Belshazzar was slain, while also naming Darius the Mede and Cyrus the Great.18 There has been much debate over the historical existence and identity of this ruler named Darius, and while our knowledge could benefit from additional discoveries and research, plausible arguments have been made that he was Cyaxares II the Mede.19 Either way, ancient records agree with the book of Daniel that the capture of Babylon in 539 BC was accomplished without a battle and that the acting king, a son of the king, was slain during a national feast.20 Thus, multiple ancient documents from Babylon, Persia, and Greece all confirm Daniel’s account of King Belshazzar as ruler of Babylon, his death during a national feast, and the fall of the city without a battle.

In sum, archaeological investigations authenticate the book of Daniel, set in Babylon, at one time the most powerful city in the world, written roughly contemporaneously with the events it describes during a transitional period in world history. Daniel records accurate historical accounts of people, places, customs, and events in sixth-century BC Babylon.

Notes

1. Cross, Frank Moore, The Ancient Library of Qumran, 2nd ed. (1961), p. 43; Scanlin, H. P., The Dead Sea Scrolls & Modern Translations of the Old Testament (1993).

2. Collins, John J.; Flint, Peter W.; VanEpps, Cameron (eds.), The Book of Daniel: Composition and Reception (2002).

3. Daniel 1:1–6.

4. Jeremiah 36:1–12.

5. There were two Babylonian kings named Nebuchadnezzar. Nebuchadnezzar I ruled ca. 1121–1100 BC. The king of Daniel’s time was Nebuchadnezzar II. For simplicity and consistency with the biblical text, he will be referred to here as simply Nebuchadnezzar.

6. Daniel 4:28–37.

7. Banquet Stele of Assurnasirpal II;Palace without Rival Inscription of Sennacherib; Dalley, Stephanie, The Mystery of the Hanging Garden of Babylon (2013).

8. Grayson, A. K., Assyrian and Babylonian Chronicles (1975) ABC 5; 2 Kings 24:10–17.

9. Berossus, Babyloniaca; Jeremiah 39:13.

10. Cf. Daniel 1:4–5.

11. Daniel 3:6–23.

12. Letter of Samsuiluna.

13. Daniel 5:1–29.

14. Cylinder of Nabonidus.

15. Verse Account of Nabonidus ME 38299.

16. Xenophon, Cyropaedia.

17. Daniel 5:28–31.

18. Daniel 5:28–6:28.

19. Anderson, Steven D., Darius the Mede: A Reappraisal (2014).

20. Nabonidus Chronicle; Cyrus Cylinder;Xenophon, Cyropaedia; Herodotus, Histories.

Titus Kennedy, PhD, is a field archaeologist who has been involved in excavations and survey projects at several archaeological sites in biblical lands, including directing and supervising multiple projects spanning the Bronze Age through the Byzantine period, and he has conducted artifact research at museums and collections around the world. He is a research fellow at the Discovery Institute, an adjunct professor at Biola University, and has been a consultant, writer, and guide for history and archaeology documentaries and curricula. He also publishes articles and books in the field of biblical archaeology and history, including Unearthing the Bible, Excavating the Evidence for Jesus, and The Essential Archaeological Guide to Bible Lands.

Get Salvo in your inbox! This article originally appeared in Salvo, Issue #71, Winter 2024 Copyright © 2026 Salvo | www.salvomag.com https://salvomag.com/article/salvo71/out-of-babylon