Two Toms (Nelson and Chalmers) on Economics as a Pastoral Issue

For years I’ve read multiple books at the same time. I won’t say it’s the best system, and I’m sure it doesn’t work for everyone. But one benefit is that the books I’m reading are often in dialogue with each other through no planning on my part. This happened recently with two Toms.

First, I started reading Tom Nelson’s The Economics of Neighborly Love. I’m currently researching the economic implications/applications of eucharistic theology (the theology of the Lord’s Supper). I’ve written about that here, and here already.

Tom Nelson is a long time pastor and the visionary founder of the Made to Flourish network. He begins his book by admitting that, for many years as a pastor, he bought into the “gap” between Sunday and Monday. In other words, he didn’t actively think much, or teach his congregation much, about the implications of their Christian faith beyond worship on Sunday.

Although Nelson had majored in business in college and had studied economics, his seminary training was silent on these issues, which served to reinforce “a dualistic understanding of the world, deepening the faulty notion that pastoral work and economic life had little in common” (3-4). Nelson eventually overcame this gap through further study, and he is now helping to lead a movement towards more wholistic ministry, helping people make connections between the Bible, culture, theology, and economics.

Economics, Poverty & Morality

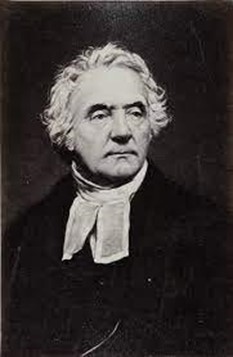

But this is not a new problem. As in many other areas, part of the problem is that American evangelicals have historical amnesia. We have forgotten (or just don’t study or care about) our theological heritage. We are not the first Christians in history to think about theology and economics. In addition to contributions of the early church, medievals, and Reformers, we can learn from the Scottish pastor, theologian, and polymath Thomas Chalmers (1780 – 1847), who addressed this in his On Political Economy.

Chalmers argues that issues of poverty and economics can never be divorced from education and morality. He begins his study by asking why pastors should care about economics:

Political Economy, though not deemed an essential branch of education for churchmen, touches very closely, notwithstanding, on certain questions, in which both the interest and the duty of ecclesiastics are deeply concerned … But there is one general application that might be made of the whole subject, and which gives it, in our judgment, its principal claim on the earnest and respectful attention of a Christian philanthropist. Political economy aims at the diffusion of sufficiency and comfort throughout the mass of the population, by a multiplication or enlargement of the outward means and materials of human enjoyment (Chalmers, On Political Economy, iii).

The full title of his book reads, On Political Economy: In Connexion With the Moral State and Moral Prospects of Society. He argues that,

… even but for the economic well being of a people, their moral and religious education is the first and greatest object of national policy …

while this is neglected, a government, in its anxious and incessant labours for a well conditioned state of the commonwealth, will only flounder from one delusive shift or expedient to another, under the double misfortune of being held responsible for the prosperity of the land, and yet, finding this to be an element most helplessly and hopelessly beyond its control (iv).

Chalmers exhorts pastors and ministers to engage in understanding economics. He argues that they have a unique role in the practical implications of economic theory:

We cannot, however, bid adieu to political economy, without an earnest recommendation of its lessons to all those who enter upon the ecclesiastical vocation. They are our church-men, in fact, who carry the most important of these lessons into practical effect. If sufficiently enlightened on the question of pauperism, they might, with the greatest ease, in Scotland, clear away this moral leprosy from their respective churches. And, standing at the head of christian education, they are the alone effectual dispensers of all those civil and economical blessings which would follow in its train. (iv-v)

Now, the mention of “pauperism” and “moral leprosy” will raise the hackles of those who have bought into the lies of the liberal-messianic state. People aren’t responsible for their poverty, are they? Before looking for stones to cast in my direction, be assured that I’ve read all the right books: When Helping Hurts, Toxic Charity, Neither Poverty nor Riches, and even Woke Church and The Color of Compromise. I know that poverty is complicated, systems are corrupt, and people are often victims of social forces beyond their control.

But … let’s turn the question around. Are wealthy people morally responsible for their wealth? Are privileged people morally responsible for how they use their wealth? Just ask the Tony Campolos, Ron Siders, Jim Wallises, and Shane Claibornes, and the answer will be a resounding YES! According to voices among the theological left, the rich are morally responsible (even culpable) because they are rich. They have moral obligations to share their wealth and to help the poor.

There are lots of Bible verses we could insert here about the necessity of sharing our wealth with the poor. But that’s not my point, and nor was it Chalmer’s point. The “moral leprosy” of pauperism (extreme poverty), as Chalmers uses the term, is the result of a multitude of factors: generational poverty, substance abuse, laziness, selfishness (on the part of both the poor and the rich), broken government and justice systems, and a lack of concern on the part of the rich. There is plenty of blame to go around.

So what’s the solution?

Economics & Shalom

Chalmers had a vision for the local church to be on the front lines of poverty alleviation. He knew that poverty was not the ultimate issue; an individual’s salvation was the ultimate issue. But he also saw the grinding conditions of early urban modernity, and he called the church to the task of loving their neighbors as themselves, in word and deed. Chalmers and his strategies have been both praised and maligned. No doubt they weren’t perfect. No doubt Chalmers had his flaws. But, to paraphrase the evangelist Jim Wilson, I like his way of helping the poor better than other folks’ ways of not doing anything at all.

Chalmers wanted the church to engage with the issue of poverty. He knew that God cares about our souls and our bodies, since God made them both. Chalmers’ Political Economy was not the final word and is definitely a product of his own time. But, like Tom Nelson, Thomas Chalmers wanted pastors to study economics in light of the Scriptures. He knew that pastors and Christian educators had a central role to play in bringing shalom to impoverished communities—both the materially poor and the spiritually poor.

We are all poor in different ways, and we all have a part to play in our local, and now global, economies. More importantly, through faith in Christ, we can participate in the divine economy, the economy of love, which should transform how we work and serve in the world. On that, both Toms would agree.

Gregory SoderbergPhD, teaches and mentors students of all ages at Logos Online School, Kepler Education, the Bible Mesh Institute, and Redemption Seminary. He writes at gregorysoderberg.substack.com and gregorysoderberg.wordpress.com.

• Get SALVO blog posts in your inbox! Copyright © 2026 Salvo | www.salvomag.com https://salvomag.com/post/closing-a-gap-for-more-wholistic-ministry