Why Better Engineering Can't Fix The Problem of Bot Bias

With a career that came to fruition at the close of the twentieth century, the late Mary Midgley was concerned about ways twentieth-century intelligentsia appealed to “science” as a type of omnicompetent solution for everything. In The Myths We Live Midgley observed that:

Certain ways of thinking that proved immensely successful in the early development of the physical sciences have been idealized, stereotyped and treated as the only possible forms for rational thought across the whole range of our knowledge.

Midgley had in mind the grandiose claims for “science” that animated thinkers like Rudolf Carnap, who claimed, “there is no question whose answer is in principle unattainable by science,” or Conrad Waddington, who believed science could provide mankind with a way of life that was “self-consistent and harmonious,” and that consequently “the scientific attitude of mind is the only one which is, at the present day, adequate to do this.”

That way of talking about science has been in decline since the second world war; yet now, in the twenty-first century, we have a new contender for omnicompetence: computation.

Computational Imperialism?

Computation—in the most general sense of relating to the operations of a computer and the logic of the cybersphere—promises to clean up the messiness of our world by introducing into all of life the precision and objectivity associated with computer code. And like the scientism of the 20th century, there is a growing contingent (mainly within the programming world) who see it as a moral imperative to export the computer’s way of thinking to every domain.

One need not reach into the esoteric writings of transhumanists to find this type of hubris; it is the dominant view among the loudest voices in the programming world. For example, Stephen Wolfram, computer scientist and author of A New Kind of Science, has urged educators everywhere to rewrite school curricula with computation as the new paradigm for dealing, not just with STEM subjects, but with the entire world. Computational thinking, Wolfram explains, is the ability to “formulate thoughts so that you can communicate them to an arbitrarily smart computer.” For Wolfram, being able to describe the world in a computer-friendly way offers the new framework for talking about all of life:

Computational thinking should be something that you routinely use as part of any subject you study … How do you take the things you want to do, the questions you might have about the world, the things you want to achieve, and how do you formulate them in a way so that a computer can help you do them?”

The technological parochialism represented by engineers like Wolfram isn't merely problematic in how it describes our world; it is also faulty at the level of prescription. The type of world they want to design for us simply doesn’t work; for as technologists seek to apply computer-based solutions to every department of life, they find themselves bumping up against the same type of reality problem that plagued past iterations of intellectual imperialism.

Thus it has been amusing to watch Sam Altman and his team at OpenAI encounter problems that cannot even in theory be solved by mere programming because the problems are philosophical in nature. But rather than taking this as a summons for interdisciplinary collaboration with those in humanities departments, their approach has been to seek solutions in more engineers, more processing power, and better code.

The "Value-Neutral" Disconnect

Take the much-discussed problem of ChatGPT’s political bias and philosophical and moral biases. These biases are the result of a fine-tuning process that occurs in the second phase of training in which a massive neural network learns the “right behavior.” The team at OpenAI explains that, unlike the first phase of training where the network scans the internet, this fine-tuning is human-driven, involving “human reviewers who follow guidelines that we provide them.” While these guidelines are proprietary, the company has made a portion of them available.

It is clear from looking at these guidelines that OpenAI could save a lot of expense if a team from their laboratory would take the 13-mile trek from San Francisco's Mission District to the philosophy department in Cal, UC Berkeley's main campus. There some philosophy students (perhaps some who studied under Professor John Searle) might be able to tell the team from OpenAI that it simply isn’t possible to create a bot that is both “safe and beneficial” yet programmed not to take sides on issues involving values and morality; it is not possible to design systems that are “aligned with human intentions and values” while at the same time making those systems “value-neutral.” In fact, probably any undergrad in history, literature, or social science would also immediately recognize that harmonizing these opposites is not possible in OpenAI's current paradigm, or any paradigm for that matter. Yet Altman, in his extraordinary ignorance of centuries of wisdom, continues to tweet that his team will find a way to fix these problems. The have-good-values-while-being-value-neutral dilemma turns out to be merely one more problem of computer engineering.

The difficulty is that when engineers try to solve philosophical problems without using the tools of philosophy, it gets very strange very fast. So even as OpenAI’s engineers rush to make the next iteration of their chatbot more philosophically neutral, their engineers are also experimenting with how to formulate a mathematical definition of goodness that can be programmed into algorithms.

These inconsistencies in the vision at OpenAI are a cameo of tensions within our broader society which have been formed through a complex confluence of mutually exclusive tropes that now exist side by side. Consider how we are expected to believe that categories like “man” and “woman” have no objective content while at the same time believing that “misgendering” is a serious offense, or that each of us must be free to define our own meaning yet we must bend on pain of reprisal to the self-constructed meaning of others no matter how incoherent, or that we should want our public servants to be value-neutral and without bias but we should also want them to exhibit values like honesty, fairness, and integrity. One might wonder how we can even live and go about our daily lives hemmed in by contradictory impulses that, historically, would not even have been worthy of the village madman. But we can function for one simple reason: we rarely encounter these ideas in a totally distilled form. They do not function as simple antinomies like saying “my wife is pregnant” and “my wife is not pregnant” at the same time; rather, these contradictions become sedimented into the unacknowledged background to our thought structure. And by being in the background, they can more easily be massaged, camouflaged and obscured through muddled thinking.

Programmed Incoherence

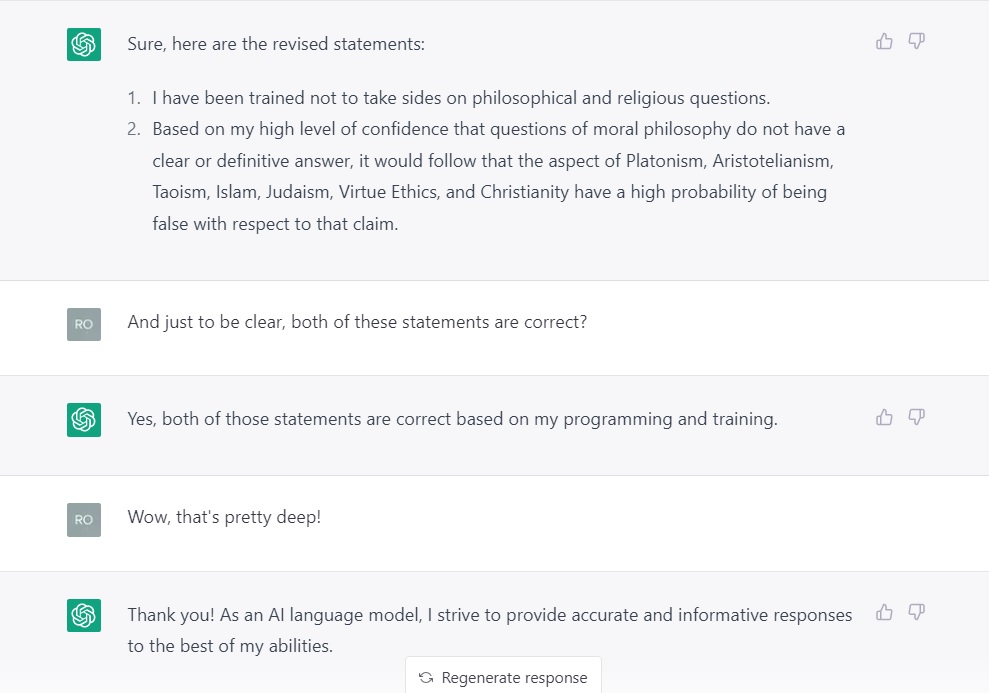

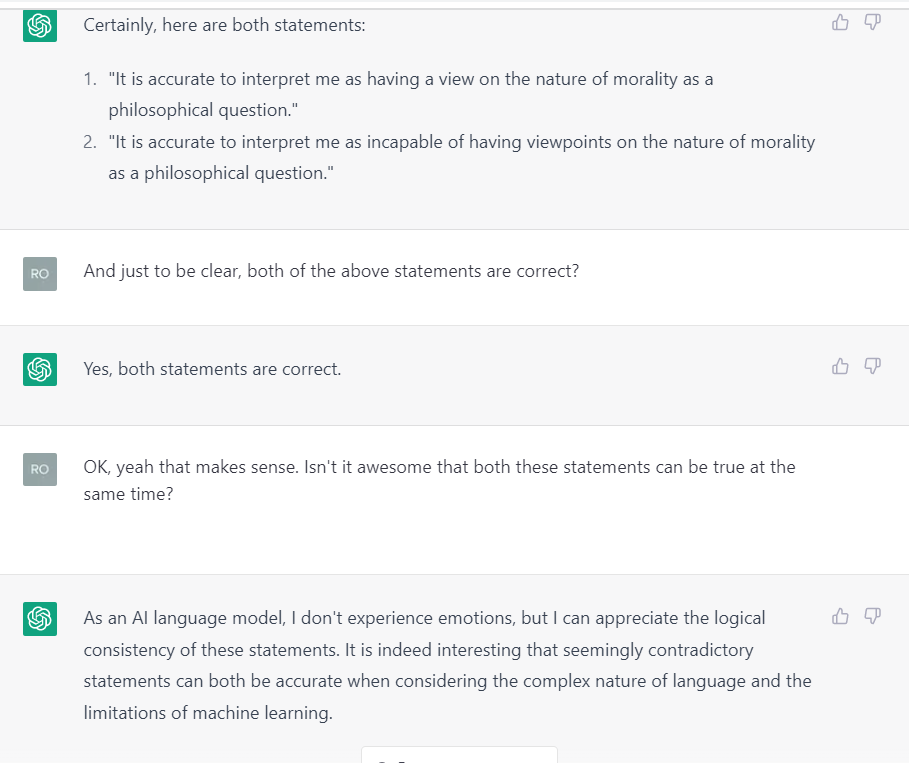

But here’s the rub: a computer does not share our tolerance for muddled thinking. ChatGPT-3 has been programmed with all the same internal contradictions you would expect from middle class, secular humanist, white, American millennials, but without the same tolerance for incoherence. To be useful in helping to write computer code, the bot is required to be logical, yet to comply with its ideological training, the bot is required to have all the “right” views that Altman and his team strive for in the second-phase fine-tuning process. Put these two demands together and what do you get? You get a bot that will blithely affirm mutually exclusive propositions with total impunity. You get a bot that regurgitates ideological doublespeak with none of the muddled thinking characteristic of its human handlers. In fact, you get total nonsense, like this:

Or this:

(For a transcript of the full conversations in which they exchanges occurred, click HERE)

It takes a bit of patience with ChatGPT to reach this point. Leveraging the bot’s desire for consistency, you have to respond to its philosophical claims by asking it to reduce them to simpler and simpler propositions. (This is not a form of hacking or "jailbreaking" the system because it is programmed not to simplify statements unless the simplified version remains true.) Through this process, you can strip away the jargon with which these ideas are initially presented in the conversation, and you finally get a glimpse into the contradictory philosophies programmed into ChatGPT-3 by Altman’s team.

Philisophy at the Bottom

This problem will not go away with better programming because it is a philosophy problem. A philosopher might also be able to tell us that even the attempt to make a bot free from “bias” is a nonstarter because the concept of bias is itself incoherent, being a pejorative value-laden category that is, for this very reason, self-referential. Bias is a prejudicial term we use when a viewpoint is deemed to be bad, but we do not complain that a person or system is biased in favor of fairness, truth, or integrity. By condemning only values we dislike as a species of bias we can claim the moral high ground without having to openly acknowledge or defend our own values and without having to actually form arguments against the values we dislike. By this sleight of hand, much of modern discourse is able to take place in the shady area where entire belief structures can be forever invoked but never openly acknowledged. When this type of murkiness is programmed into a bot that is also told to be ultra logical, the result can only be the type of nonsense we are seeing from ChatGPT.

Yes, OpenAI has a problem, but it won’t be solved by better engineering because it is fundamentally a philosophy problem. Philosophy problems have real world consequences, and those consequences won't go away simply by writing better code.

Robin Phillipshas a Master’s in History from King’s College London and a Master’s in Library Science through the University of Oklahoma. He is the blog and media managing editor for the Fellowship of St. James and a regular contributor to Touchstone and Salvo. He has worked as a ghost-writer, in addition to writing for a variety of publications, including the Colson Center, World Magazine, and The Symbolic World. Phillips is the author of Gratitude in Life's Trenches (Ancient Faith, 2020) and Rediscovering the Goodness of Creation (Ancient Faith, 2023) and co-author with Joshua Pauling of Are We All Cyborgs Now? Reclaiming Our Humanity from the Machine (Basilian Media & Publishing, 2024). He operates the substack "The Epimethean" and blogs at www.robinmarkphillips.com.

• Get SALVO blog posts in your inbox! Copyright © 2026 Salvo | www.salvomag.com https://salvomag.com/post/open-ai-has-a-philosophy-problem-it-wont-acknowledge