Lessons from the Map Wars

I love maps. My favorite map of those I possess is a topographical map of the sea floors. My second favorite is a reproduction of a 1570 world map, in which both Japan and South America are shaped like potatoes, and Australia is connected to Antarctica.

So, having established my reputation as an illustrious Map Scholar, allow me to obliterate your conception of our world.

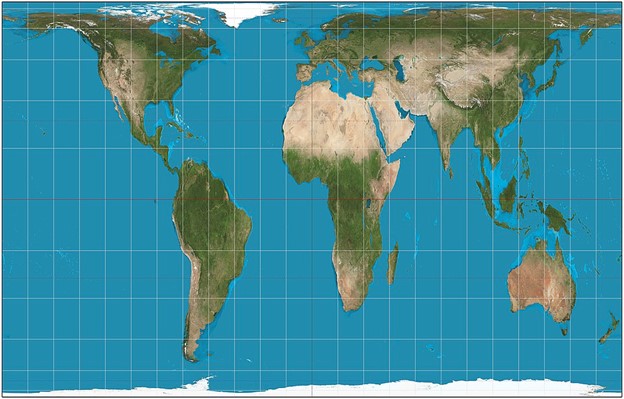

Here is the world you’ve always known:

And here is the real world, as it actually looks:

Undoubtedly, your jaw has dropped in shock! Everything you thought you knew about the world has been swept away like chaff. Greenland isn’t really larger than Africa. Antarctica isn’t really larger than Eurasia. Your whole life has been a lie.

Strawmaps

If you want to raise your hand at this point and suggest that neither of those two maps looks anything like the world as you know it to be …

Well, you are right, of course. Neither map shows the actual world. The world is a globe, and both maps distort it in different ways in order to display it as a rectangle.

But you’re not the first person to have “enlightenment” pressed on you in this way.

“When Boston public schools introduced a new standard map of the world this week, some young students felt their jaws drop,” The Guardian reported in 2017. “In an instant, their view of the world had changed.” The school had decided to phase out the old Mercator maps and replace them with Gall-Peters maps. This change, according to school officials, was “the start of a three-year effort to decolonize the curriculum in our public schools.” The article quotes a “delighted” antiracism lecturer: “The Mercator projection showed the spread and power of Christianity and is standard. But it is not the real world at all.”

The problem with the Mercator projection was that it stretches out the landmasses closer to the north and south poles, making them disproportionately large compared to landmasses nearer to the equator – thus diminishing the “Global South” in the eyes of thousands of schoolchildren.

If you were to point out that one has to choose between preserving accuracy of size or accuracy of shape when making a map, and that Gerardus Mercator had to preserve shape instead of size, not for political reasons, but so that navigators could use his map effectively – the reply would be something like, “Exactly. The very purpose of this map was to guide colonialists and aid them in colonizing the world. The map is western imperialist to the core.”

Boston Public Schools was only the latest case of an institution adopting the Gall-Peters projection in rejection of the insidious Mercator projection. Since the 1970s, various agencies and institutions have adopted it, including UNESCO and the World Council of Churches.

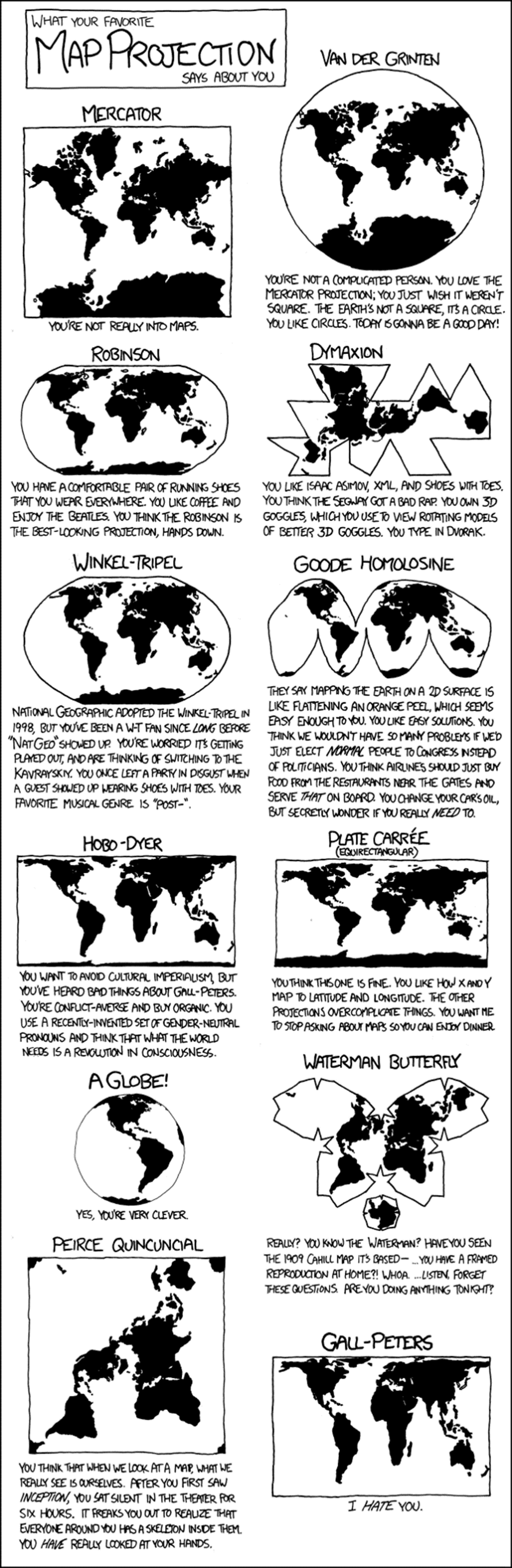

Every time this happens, people who know anything about maps get annoyed or confused. There are many maps to choose from besides the Mercator or the Gall-Peters, including some that are superior to both (and others that are just funny). Take a look at just a few of the endless options:

With so many maps to choose from, why does the choice have to be between two inferior options? Well, as map historian Mark Monmonier points out, the Mercator projection is a useful strawman in our contemporary “Map Wars.” It’s much easier to push for the Gall-Peters map if the obviously flawed Mercator is presented as the only alternative.

The Moral of the Story

I am interested in this story, not just because I like maps, but also because the story serves as an illuminating visual illustration for what is often going on when ideologies clash. I suppose it’s not surprising that it would – after all, an ideology is a kind of map, in a way. A map is a two-dimensional representation of a multi-dimensioned reality – and in some ways, so is an ideology. A map is, quite literally, a view of the world, i.e., a “worldview.” So what happened with the maps is instructive.

To start with: the root of the problem with the maps was that maps were two-dimensional. Likewise, the root of the problem in many ideological conflicts is that the ideologies are two-dimensional. With both wall maps and ideologies, this can’t be avoided. Because a statement about reality is simpler than reality itself, language cannot depict its referents with perfect accuracy. Something must be stretched, something else shrunk, or something cut out altogether.

This inconvenient fact may in part be why postmodernists say there is no such thing as “absolute truth.” And, as strange as it may sound, there is a limited sense in which that is … well, true. Think about it. Even the classically “true” statement “the sky is blue” is not really unequivocally true. Almost half the time – or, in half of the world – the sky really looks black, not blue.

It would be easy to sit here and list other ways in which the sky is not blue, but you probably get the point. We can grant that there is no “absolute truth” if “absolutely true” is defined as “unambiguously conveying all aspects of a reality.” That, in itself, is a modest and innocuous statement. Human language is inherently limited and inherently ambiguous. That’s why puns and poetry are possible.

But, at the risk of oversimplifying it, postmodernist philosophy, at least the Critical Theory manifestations of it, makes a leap from there, and concludes that because there is no absolute truth, language is primarily a tool of domination, not truth-seeking. I could be misjudging them, but that seems to be the attitude of the sort of people who push for Gall-Peters maps in classrooms: “No map is really true, so we might as well choose the map that fights for our side.”

It’s true, of course, that language can be merely a means to power. But that doesn’t mean it should be. To say that language is merely a tool of domination is to say that human interaction itself is merely a tool of domination. And isn’t that a sociopathic – or even diabolical – way of looking at human relationships? If, instead, communication is about working together to understand the world better, then the best way to gain and communicate the truth is to look at reality from multiple angles. Being on the side of truth need not mean being on the side of one viewpoint. A single reality can and should be seen from different angles if it is to be understood.

In other words, what we want is not new maps, but rather, a globe. (The smart aleck in the cartoon above was correct.) A globe is not a complete representation of the world any more than a map is. Yet a globe is superior to a map, simply because you can view it from multiple angles.

Of course, once you walk over to the viewpoint of your opponent, you might see that his difference of opinion was not caused by the different vantage, but merely by his bad vision. But you won’t know until you get there.

The trouble is, you won’t want to enter another point of view, even provisionally, if you see it as belonging to The Enemy. That is why so many debates about important issues end up revolving around simplistic, two-dimensional portraits of the world. If someone you don’t like presents a simplistic, two-dimensional portrait of the world, you are at risk of instinctively reacting against it in disgust and moving to the opposite view – like choosing the Gall-Peters because you hate the Mercator. But the result of that is just two people with two shallow worldviews in conflict.

This implies a somewhat odd conclusion: that if you want to seek the truth, you should begin by loving your enemies. There’s no way around it. Hatred is blind and does not know that it does not know. Love may at least see. Hatred keeps our perception of the world flat, but love makes the world go round.

(Pun intended.)

Further Reading

- Cara Giaimo, “Why Map Historians Are Annoyed With Boston Public Schools”

- Mark Monmonier, “How to Lie with Maps”

- Denyse O’Leary, “Why Can’t Winston Count?”

- Terrell Clemmons, “Whirled Views”

Daniel Witt (BS Ecology, BA History) is a writer and English teacher living in Amman, Jordan. He enjoys playing the mandolin, reading weird books, and foraging for edible plants.

• Get SALVO blog posts in your inbox! Copyright © 2026 Salvo | www.salvomag.com https://salvomag.com/post/the-problem-with-the-maps