The 15-Minute Transgender Consult

Jessica was one of my patients on a busy day in the clinic. Self-conscious about her weight and the fashion limitations of her socioeconomic class, Jessica clearly fell somewhere among the vulnerable lower rung of the junior-high-school cultural food chain. As her single and disabled custodial grandmother spoke, Jessica sat motionless, arms crossed, staring furiously at the floor. From a previous visit I had discerned that in the gray zone of adolescence, her emotional maturity lagged toward the child end of the spectrum, a place I wish young patients like her could be left in peace, unmolested, to naturally mature at a slower pace than some of their peers. But seeing her adult woman’s body and the smartphone clutched in her hand, I knew that simply wasn’t an option for her.

“Doc,” her grandmother began, “there’s some crazy things going around with these kids. Jessica is saying she might be a boy. That’s just plain nuts! She had her first period over a year ago! Can you talk to her?”

I said nothing, giving Jessica room to respond. She remained silent as I noted the new and unflattering straight bob cut, loose sports jersey, and boy’s gym shorts she was now wearing.

“What does that mean to you?”

As the silence grew uncomfortable, I spoke. “Jessica, I’d really like to know what you are feeling. Your grandma just told me you think you might be a boy. Do you feel like you are a boy?”

She shrugged. “Not exactly. But I’ve never had a boyfriend, and I don’t really want one. I just don’t feel like I’m a normal girl, either.”

Grandma spoke again, “Doc, some older girls have made her feel bad ‘cause she ain’t started dating yet. Gawd, she ain’t but 14! They told her it’s probably ‘cause she’s a transgender.”

“Jessica, what does that mean to you —transgender?”

Another long pause, then finally a scripted yet tentative answer: “That I was born in the wrong body? That I’m really a boy and I need to start living as a boy to be true to myself?” It was clear that internet influence was part of the mix.

“Do you think that is possible? Do you believe that you can become a boy?”

Another shrug, but this time she turned to look at me, anger giving way to engagement. “Don’t some people take medicines and have operations that change their sex?”

“They do change how they look,” I said, “and they lose aspects of how their body would normally function —but they do not actually become the other sex.”

Jessica frowned inquisitively.

“Girl” and “Boy”

“Do you mind if I explain to you why I don’t believe that sex change is possible?” I asked. “Many people disagree with my perspective, and you may as well, but I believe you will be much smarter about what is going on if you will let me share some medical knowledge with you.”

She nodded. I had her step off the exam table and sit in a chair beside me, leaving us a long stretch of blank exam-table paper as a notepad. I drew two rectangles, placing an “XX” in one and an “XY” in the other.

“Do you understand these symbols?” After a moment she touched the left box, then the right, and correctly tagged them “girl” and “boy.”

I smiled. “Yes! Those two letters represent the sex chromosomes that we all have.” Below each rectangle I added her words along with the circle symbols for female and male. “Chromosomes are what make up our DNA, the packets of genetic information that give each of us our unique physical blueprint, or body plan. Height, natural hair color, and sex —male or female —are all largely determined by the chromosomes we are born with. Our DNA has 23 pairs of unique chromosomes from the time we are conceived until the day we die. You are aware that our bodies are made up of building blocks known as cells —right?”

She nodded. “We covered that in science class.”

“Good. How many cells do you think you and I have in our bodies?”

“A lot . . . million, maybe?”

“How about over 30 trillion?” Her eyes widened as I wrote a “3” followed by 13 zeros.

“What do you think is an important difference between each of those cells in my body as a man, and every one of the trillions of cells in your body as a woman?”

“Testosterone?”

“No, we both have testosterone, although as a male I certainly have more. The foundational difference is that the 23rd chromosome set in every single cell of my body, every cell except the red blood cells, is XY —and always will be. It is the thing I share with all males. You and your grandmother here both have XX pairs on chromosome 23 of every cell, just like all women everywhere of all time. Nothing can ever change that. That is why I do not believe sex change is real or possible. It’s a false promise.”

“Don’t puberty blockers and hormones change all that?”

“Not at all. Your body can be manipulated by pills and shots of artificial hormones that can make a female body seem more masculine in characteristics like voice tone, hair growth patterns, and muscle development, or a male body look and sound more feminine. But that never changes an XX to an XY, or vice versa. Similarly, a surgeon can remove normal body parts so that a female loses the capacity to release an egg, receive fertilization, carry a baby to birth, or produce breast milk, and surgery or chemicals can take away a boy’s capacity to produce sperm and become a father. But what a surgeon can never do is give a female the capacity to make sperm or a male the capacity to ovulate and carry a pregnancy.”

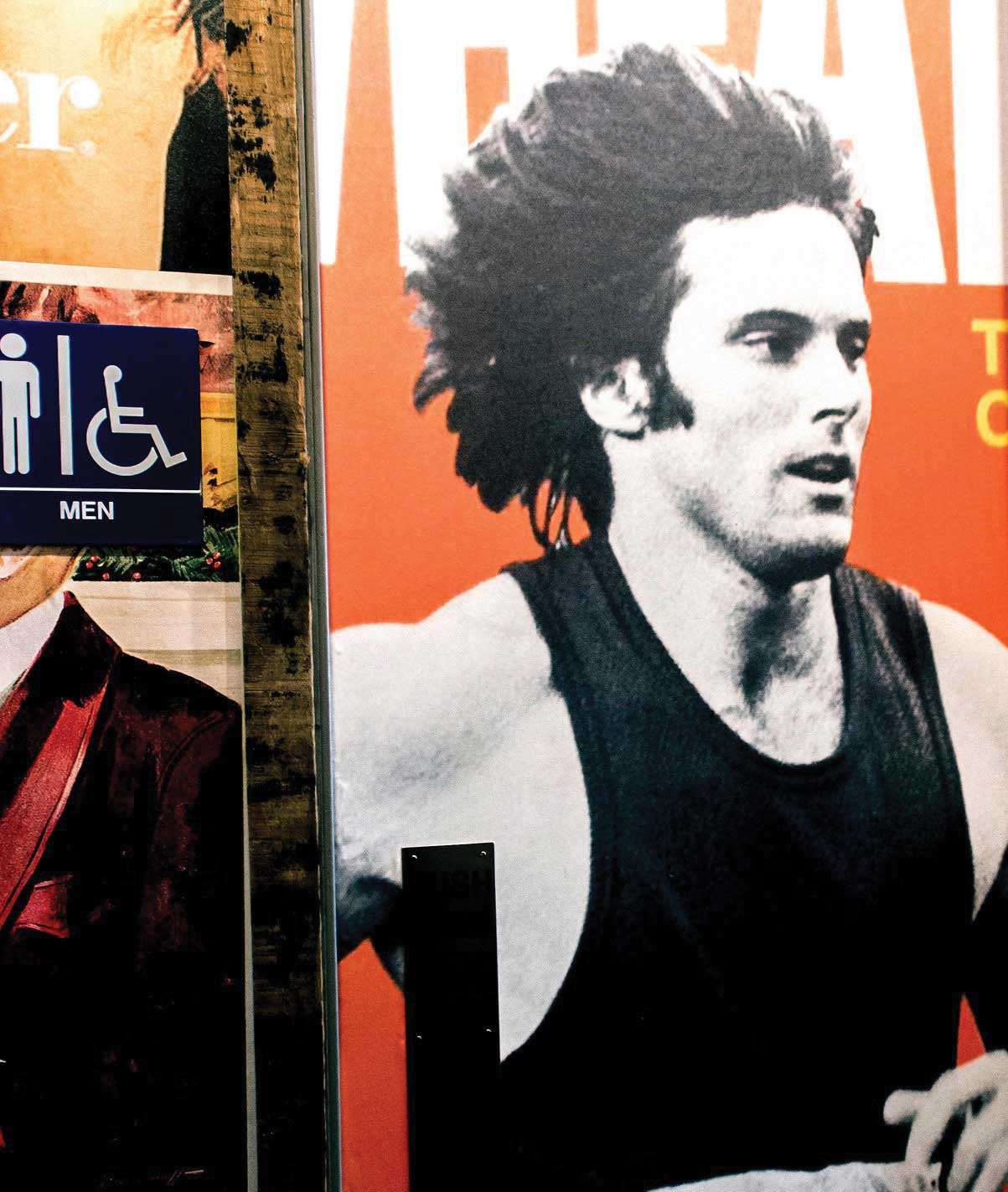

I opened my iPhone and pulled up a picture of an orange 1978 Wheaties box featuring a long-haired, side-burned, tank-top-clad masculine athlete. The caption read, Bruce Jenner: Olympic Decathlon Champion. “Recognize him?”

She studied it for a moment then shook her head, no.

“That is Caitlyn Jenner when he was 28 years old,” I said. “My brother and I ate breakfast from a box just like that after watching Bruce Jenner take the gold at the Montreal Olympics in 1976. We admired him as the greatest athlete in the world. The man in this picture now chooses to wear women’s makeup and dresses —and I support his right to do that just as I support his right to change his name to Caitlyn —but he still has an “XY” in every single cell of his body. Underneath the women’s clothes and jewelry, Caitlyn still inhabits a male body. Think of how important that is. Unlike you, Bruce Jenner was never a girl. He has never menstruated, and he never will.

He grew up as a boy and matured to become an athletic man who won gold medals and fathered six children. Do you think a woman could do that?”

She smiled thoughtfully.

I continued. “Caitlyn Jenner is a male who today chooses to impersonate a female. That is what it means to be transgender. Drugs and surgery can offer someone like you the means to become a medically damaged female who, with the aid of drugs taken for the rest of your life, has the option to live as if she is a male. If you did that, you might fool some people, but you would never fool yourself. Nothing can give you XY genes. Nothing can make you a male, and you will always know that.”

“What about non-binary?” she asked. “Aren’t some people neither . . . or both?”

“When I deliver a baby, it is always either XX or XY, a boy or a girl, and each will be so their entire lives. The binary nature of sex is true of all mammals, including humans. Neither I nor any other doctor guesses or chooses any baby’s gender at birth. The only exceptions are rare genetic or metabolic diseases where the sex is unclear. But we shouldn’t treat those unfortunate cases as ordinary any more than we would treat a cleft palate or a condition where someone is born with a malformed arm or leg as just a normal variation. We treat and correct what birth defects we can, and we provide support and care no matter what.”

Feelings

“But if I don’t feel like a girl, that seems unfair.”

“Feelings often change. At fourteen there is no reason you should feel the need to have a boyfriend. What’s the rush? You are still growing and changing in both your mind and your body. As for fairness, there are many things none of us get to choose. Life is like that. We have no control over what decade we are born in, what country we are born in, the first language we learn, the ethnic heritage or skin tone we get from our parents, or what sex we are. Some people are born handicapped, through no fault of their own. What we all have in common is the challenge of making a good life with what we have, and you have an XX 23rd chromosome. You are a female and a woman —which is truly a wonderful thing.” I wrote her name under the female side of our diagram.

“What about gay people? Are they real?”

“To be gay means you have a sexual attraction to members of the same sex. Lesbians prefer to have intimate relationships with other women, and gay men are attracted to other men. But lesbians generally accept their bodies as being female, and gay men still see themselves correctly as males. Transgenderism is different in that it is a false idea that asks us to believe we can alter reality by supposing that biological sex is not real. When people turn to drugs and surgery to live out an illusion like transgenderism, the result can be severe physical and emotional harm that cannot be undone. That is wrong and unnecessary. I don’t want that to happen to you, or to anyone.”

I considered giving her examples of people who deeply regretted transgender surgeries that could not be undone, or sharing with her statistics showing that people who take drugs or undergo surgeries in an attempt to change their sex tend to have higher rates of psychological and emotional problems than those who struggle with gender-identity issues but forego such treatments. But I sensed that I had given her as much as she could absorb for one day, so I left it at that.

Caring for the Vulnerable

Jessica demonstrates how insecurity among the young is fertile ground for transgender ideology. She lacks a father figure. She may be somewhere along the autism spectrum. Or she might simply be one of those who has trouble fitting in. Past trauma, too, is a common vulnerability. Whatever the factors in her situation, she was susceptible to outside influencers, in this case older girls, offering what seemed like a plausible explanation for her adolescent discomfort. What I was able to offer was perspective regarding a path that intrigued her, but about which she understood very little.

For the kids to be alright, they need the presence and guidance of adults —caring, rational adults who are vigilant and ready to listen so that the young person feels heard and seen but who are also ready to provide calm, clear reasoning as to why they should doubt the whole premise of transgender ideology, rather than doubting the reality and goodness of their own bodies.

Bruce Woodallis a rural family physician. He and his wife Dale, also a physician, divide their time between primary care in Texas and six months abroad each year with Free Burma Rangers. Bruce has delivered over 3,000 babies and has never once guessed or randomly assigned the sex of a newborn.

Get Salvo in your inbox! This article originally appeared in Salvo, Issue #68, Spring 2024 Copyright © 2026 Salvo | www.salvomag.com https://salvomag.com/article/salvo68/identity-checkup