Worldview Literacy Is an Essential Skill for Making Sense of Postmodernity

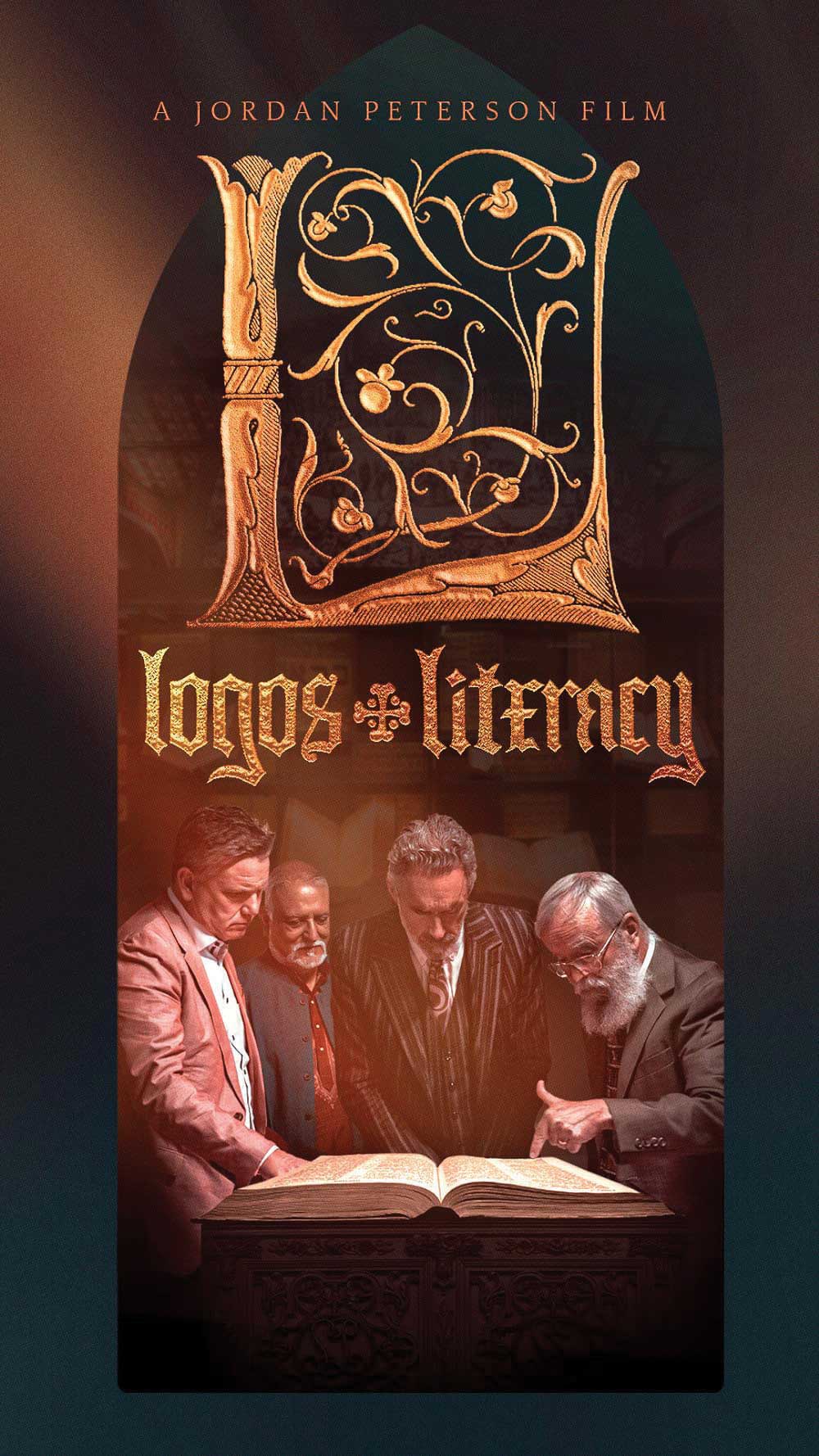

The 2023 documentary Logos and Literacy: The Amazing History of the Bible follows along as Jordan Peterson tours the Museum of the Bible in Washington, D.C. As a self-described cynic, Peterson admits that, prior to his visit, he had expected to find “a backwoods fundamentalist enterprise.” But the title captures his astonishing discovery that the Bible was key to the spread of literacy around the world.

The Chinese had printing technology around AD 700, but the watershed moment for world literacy didn’t come about until Johannes Gutenberg began printing Bibles in the 15th century. Aided by the European Reformation that followed, Gutenberg set off a worldwide explosion in reading. This raises a question: why didn’t it happen in 8th-century China?

Ultimate Reality

The answer to that question has everything to do with worldview. Vishal Mangalwadi explains that ancient Buddhists printed thousands of pages of their holy book, the Tripitaka, but they didn’t read them:

Those books didn’t inspire the confidence that words can lead you to truth, that ultimate reality was word —logos. Nobody was reading the books because Buddha taught ultimate reality as silence, not logos, not word. So what these priests were doing was rotating the bookcases and meditating on the sound of rotation. The sound of these sacred books rotating would empty their mind, bring silence, get rid of thought.

At the risk of oversimplifying it, a worldview is a proposed explanation of reality. Every worldview begins with some postulated “ultimate” and then explains everything else by reference to it. Judeo-Christian theism holds that ultimate reality is a self-existing Being with a mind —a living logos. Logos can mean “master plan,” “understanding,” even rationality itself. If ultimate reality is logos, there is a rational world to be engaged with and truth to be known. If ultimate reality is silence, by contrast, there is no reason to seek knowledge.

Moderns might laugh at ancient priests listening to rotating bookcases, but apart from their worldview context, many contemporary developments can be equally inexplicable. Materialism, the prevailing secular outlook today, assumes that everything, including human beings and even human thought, can be explained by reference to matter and energy. Materialist presuppositions explain why some people erroneously confuse machines with sentient beings (see “Sense & Insentience,” p. 29) or turn to robots for intimacy and caring behavior (“The Digital Odyssey,” p. 36 and “Saving Face,” p. 58). Materialism also explains astronomer John Gribbin’s comment that “Nobody has been able to think of a reason” why all the right conditions for perfect solar eclipses happened to come together in our time and place in the universe (“Signs in the Sky,” p. 40).

Understanding

What Gribbin ought to say is, “I am unable to think of a reason why the right conditions for perfect solar eclipses happened to come together in our time and place.” And the reason he can’t do that is because his worldview blinds him to the possibility of an intelligent Being whose essence is logos. Notice how materialism limits his understanding and defines how he interprets reality. That’s how a worldview works.

We bring you analyses on cultural happenings such as these in hopes of helping you and yours cultivate worldview literacy. Also, as you will see on the following page, we are bringing back Letters to the Editor (Incoming, p. 6). Good thinking is always a group enterprise, and we invite you to dialogue with us in the endeavor. Lord willing, may we together set off an explosion of worldview literacy that spreads wherever the fertile soil of good thinking can be found.

Terrell Clemmonsis Executive Editor of Salvo and writes on apologetics and matters of faith.

Get Salvo in your inbox! This article originally appeared in Salvo, Issue #68, Spring 2024 Copyright © 2026 Salvo | www.salvomag.com https://salvomag.com/article/salvo68/sense-sensibility